When climate policymakers think about forests, they are usually considering carbon sinks or sources: Forests release carbon when they are cleared, burned or degraded, and absorb carbon as they grow. However, a new four-part forest report from World Resources Institute (WRI) and its partners challenges these assumptions.

Published for the Cities4Forests movement and entitled Not Just Carbon: Capturing All the Benefits of Forests for Stabilizing the Climate from Local to Global Scales, the report demonstrates that policymakers must heed clear evidence that forests are even more important for the climate than previously thought.

A growing body of research reveals that forests interact with the atmosphere in many ways other than through the global carbon cycle, affecting rainfall and temperature from global to local scales.

In fact, the non-carbon effects of forests are not only essential for fighting climate change, but for food and water security, human health and the world’s ability to adapt to a warming planet.

Important non-carbon effects often get overlooked

Of course, the positive carbon benefits of forests are still big news — just not the whole story.

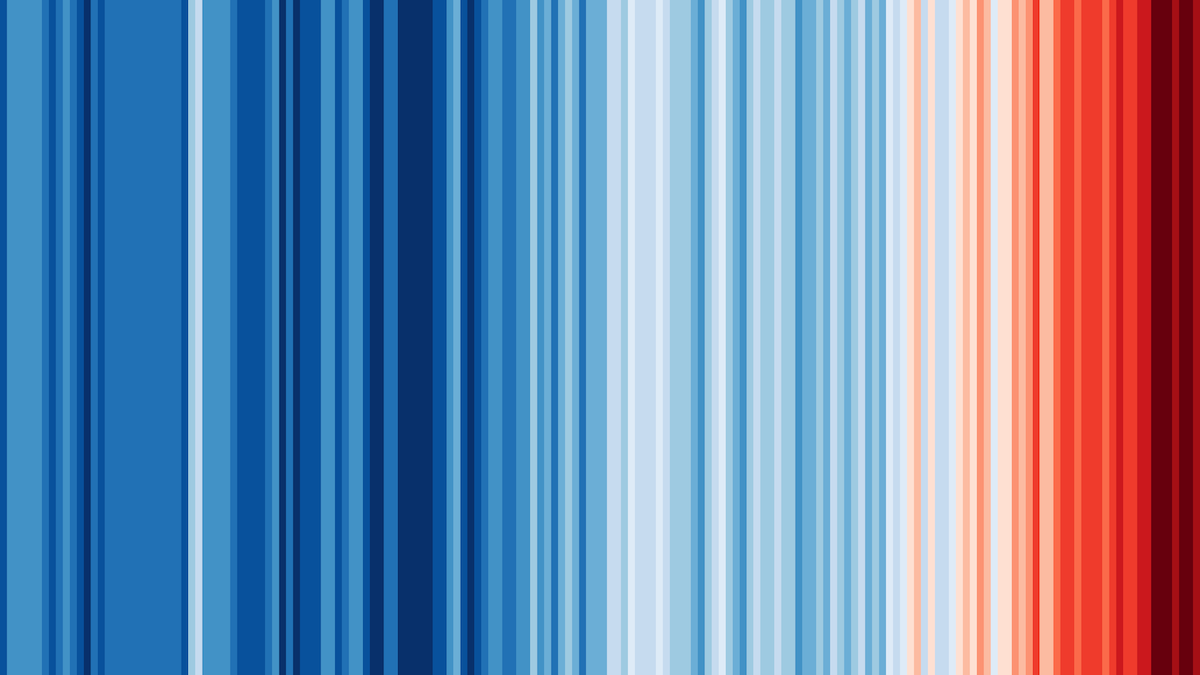

Reducing CO2 emissions from forest loss and enhancing carbon removals through forest restoration are critical to achieving global climate goals. Doing so would achieve about 6.5 gigatons of CO2 per year of climate mitigation by 2030. This equates to about one-third of the mitigation required from all sources to keep global warming to or near 1.5°C (2.7°F) — the limit scientists say is necessary for preventing the worst effects of climate change.

However, forests also have many non-carbon effects that carry important, yet often overlooked, local, regional and global implications — and not all of them push in the same direction as CO2 effects.

According to WRI, some of the main non-carbon processes through which forests affect the climate include:

- Albedo, or how much of the sun’s energy is reflected into space from a particular surface, affects how much solar energy is absorbed. Light-colored surfaces return a large part of the sun’s energy back to the atmosphere and can have a cooling effect (high albedo). Dark surfaces absorb the rays from the sun and can be warming (low albedo). Dark green tree cover usually absorbs more energy than snow cover, crops or bare soil, warming the air as leaves release that heat, much like the heat radiating from a blacktop road.

- Evapotranspiration, or the role of trees in releasing moisture into the air, produces a cooling effect. This happens when water evaporates from the surface of leaves, as well as when water pulled up through the tree’s roots is released through tiny pores in leaves. These processes function as natural air conditioning, cooling Earth’s surface and near-surface air.

- Surface roughness, or the unevenness of a forest canopy, affects wind speed and turbulence. This turbulence helps lift heat and moisture away from Earth’s surface, providing a cooling effect.

- Aerosols are tiny particles, such as pollen, released by forests. Trees also produce chemical compounds, like the ones that give Christmas trees their signature aroma. These particles and compounds interact with the atmosphere in complex ways, changing ozone and nitrate concentrations and affecting the colour of clouds.

Together, albedo, evapotranspiration, surface roughness and aerosols also affect the generation of clouds, which in turn increase albedo with a cooling effect.

Deforestation in one country can lead to drought in another

One of the key points made in the report is that tropical forests have an overall global cooling effect — not only from their carbon removal, but also from high rates of evapotranspiration and their ability to stimulate cloud cover (and thereby increase albedo).

When we account for the non-carbon effects of tropical deforestation, their estimated contribution to global warming increases by 50% compared to carbon effects alone. In short, keeping tropical forests standing provides massive ‘bonus’ global cooling that current policy ignores.

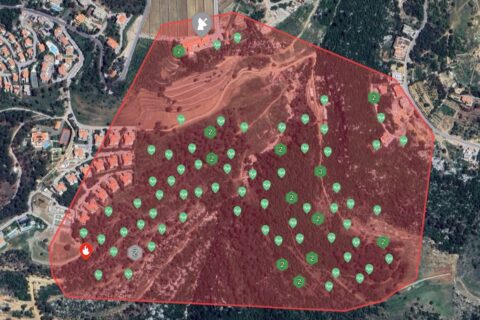

Furthermore, the effects of deforestation on rainfall patterns occur at regional and local scales and depend on factors such as the size of the area deforested and wind patterns.

Large expanses of tropical forest — such as those in the Amazon and Congo Basins — recycle moisture in the atmosphere as it passes across the continents, falls as rain, and is then released by trees through evapotranspiration.

As a result, large-scale deforestation can disrupt this cycle, exacerbating droughts in downwind areas, even hundreds of miles away. So, for example, researchers estimate that forests in Brazil provide 13-32% of annual precipitation in the downwind countries of Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay and Argentina.

Deforestation in Brazil can therefore be a major contributor to drought in these countries.

What are the implications of ignoring these other impacts?

As the report states, these additional, positive impacts are being ignored, at present.

National, regional and local climate mitigation and adaptation policies do not yet account for the non-carbon effects of forests. By failing to take these effects into account, current policies systematically undervalue forests’ climate services, fail to anticipate the full range of climate risks associated with deforestation, and result in an inequitable allocation of responsibilities and resources for climate action within and between nations.

For example, national climate accounting based on carbon alone results in overstating the global cooling effects of forests in countries at higher latitudes — such as those in Canada, Russia, Scandinavia and the United States — and understating the cooling effects of forests in tropical countries.

There is a lack of regional intergovernmental institutions in place with the power to address the cross-border effects of deforestation on rainfall.

Also, thinking about global warming only in terms of global average temperatures masks significant local impacts of deforestation on rising local average and extreme temperatures.

What can policymakers do to better value forests?

The good news is that there are many opportunities to address the full range of forests’ climate services within the mandates of existing institutions and processes. The report details a number of options available, both in terms of global and national climate policy arenas, as well as ways of covering the shortfall in existing institutions for managing impacts of deforestation on rainfall, by drawing on water and air pollution resources and mechanisms.

In addition, national and local authorities responsible for land-use planning and agricultural policy offer potential for integrating forests’ non-carbon climate benefits into existing programmes.

The non-carbon effects of forests on temperature can also be incorporated into national and local adaptation planning. To date, concern about the effects of climate change on human health has focused on increasing global average temperatures, such as expanding ranges of disease vectors and increased exposure to heat stress in urban heat islands. If public health officials understand the magnitude of risks posed to workers and communities in rural areas due to forest cover loss and resulting temperature extremes, they can help advocate for forest protection.

Why it is necessary to take action, now

The Not Just Carbon report makes it clear that the science of forest-climate interactions is complex. It also acknowledges that further research is needed to fully estimate the additional economic benefits of protecting forests to stabilise the climate, beyond reducing carbon emissions.

Nevertheless, the risks to climate stability from losing forests’ non-carbon services more than justify taking action, now. It is also clear that a failure to act will exacerbate existing inequities within and between countries.

Ultimately, forests are so much more than just carbon. It is time they were appreciated for their full climate value — to benefit the people who live and work in and near them, hundreds of miles away, and all around the world.

Further Reading:

- More about World Resources Institute (WRI);

- More about the Cities4Forests movement;

- Read and download the full Not Just Carbon report;

- Also on SustMeme, Reforestation grows towards goal of 100M trees;

- Also on SustMeme, Football pitch of rainforest lost every 6 seconds;

- Also on SustMeme, Crowdsourcing AI to fight deforestation;

- Also on SustMeme, Carbon offset prices could jump 50-fold by 2050;

- Also on SustMeme, Bioplastic tree shelters to solve planting waste problem;

- Also on SustMeme, Tree-planting punks: First carbon-negative beer business.

>>> Do you have sustainability news to broadcast and share? If you would like to see it featured here on SustMeme, please use these Contact details to get in touch and send us your Press Release for editorial consideration. Thanks.