In this SustMeme Guest Post, Kelly Hunte, attached to the new Small Island Developing States (SIDS) hub, questions whether unlearned lessons on funding promises mean the same old mistakes will get made again.

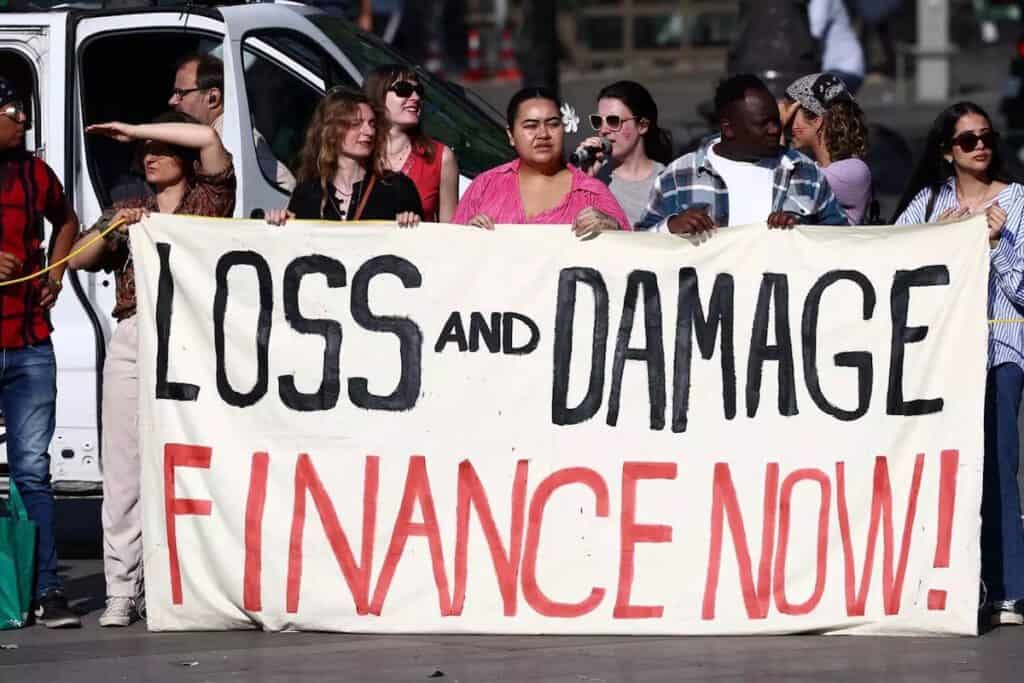

KH: At time of writing, the total for pledges to the Loss and Damage Fund amounts to US$765.59, made by some 27 counties to date. The key word here, though, is ‘pledges’; which is not the same as ‘payments’.

So, what exactly is the Fund designed to do; and why should we be sceptical about its prospects for success?

Fund a decade in the making

In recent history, the Loss and Damage Fund (LDF) was first announced at the 2022 Conference of the Parties in Egypt (COP27), then officially enshrined in a formal agreement one year later at COP28 in Dubai.

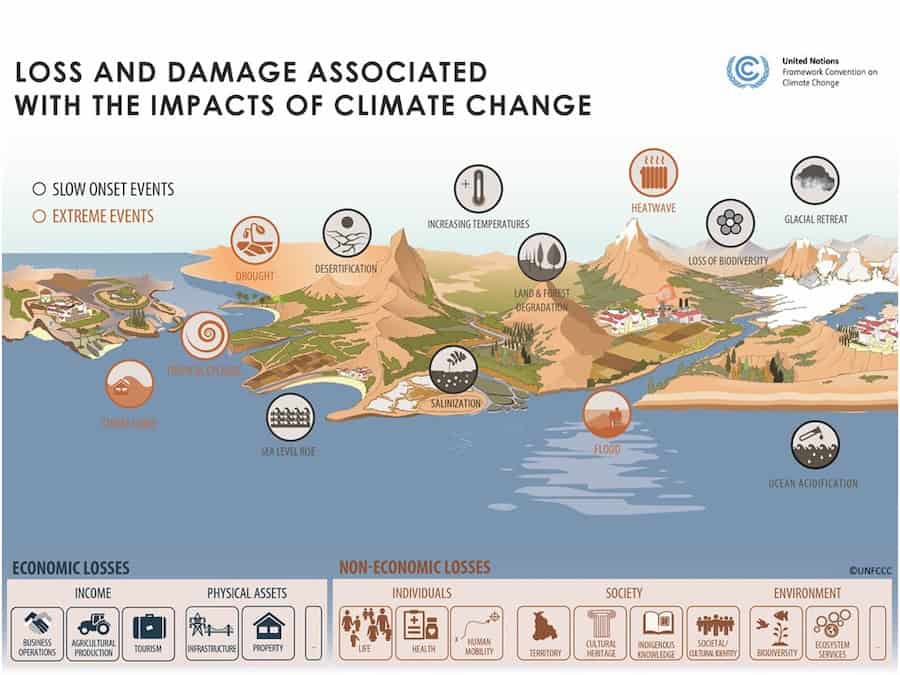

However, origins of the LDF go back a decade earlier to COP19 and the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage (WIM) in United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) 2013.

This original mechanism was set up due to the fact that it had become more and more clear that existing frameworks to deal with all climate change impacts were not enough.

Building on momentum from Warsaw, Article 8 of the Paris Agreement sought to enrich understanding, action and funding for LDF thereby giving it recognition within international legal frameworks.

Lessons have gone unlearned

The modern-day LDF is aimed at financially supporting countries that face the most risk from climate change so that they can deal with both the immediate and long-term effects of loss and damage.

The issue is how this new fund is being capitalised mostly through voluntary contributions from Developed Countries. It’s like we haven’t learnt anything from capitalisation of the Green Climate Fund (GCF).

Countries pledged significant funds in the past for capitalising the GCF, but what is pledged is never paid; and history has now repeated itself with the US rescinding their pledge to the GCF after the recent election.

Sadly, it is easy to forecast that the LDF faces the same fate. The US has already quit the Board of the LDF ahead of the next meeting scheduled to take place in April. It will not be long till their pledge is rescinded.

So, what alternative funding approaches do we have?

From bonds to philanthropy

Well, many scholars have offered additional ways in which the LDF could be capitalised and re-capitalised given that past experiences of relying on voluntary pledges always come up short when it is time to pay.

Other mechanisms such as climate risk insurance schemes, catastrophe bonds, and green bonds have all been tabled as options for diversifying the resource mobilisation strategy for the LDF.

Philanthropic sources could also be considered as possible funding sources. However, once again the track record here is poor, with the GCF not able to mobilise much funding from private or philanthropic sources for its re-capitalisation since many of these organisations appear to have no real interest in climate change.

In short, we shouldn’t get our hopes up on that!

How will access be triggered?

One key issue that needs to be addressed is how countries will actually access these funds, in practice.

The use of parametric insurance triggers has been discussed as a mechanism to determine LDF access. These trigger payouts when specific conditions are met, such as certain levels of rainfall, or wind speed.

There are also parametric insurance products for damages after an earthquake, if the temperature (heat) rises past a certain level, plus floods and tropical cyclones (with coverage for storm surge inundation).

One of the challenges with parametric insurance triggers is that the payments often do not fully reimburse the policyholder for the loss suffered; and if specific conditions are not met, no pay out is given. As impacts of climate change intensify; insurability for certain climatic events will inevitably decrease over time.

Who is eligible for funding?

The other burning issue with the LDF is which countries will even be allowed to access funding, in principle.

Many have argued the countries that contribute the least to the problems of climate change should be the ones to benefit from the LDF. However, many Developing countries argue they too should all have access.

The reality is that the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and Least Developed Countries (LDC) are ultimately the places, nations and communities that suffer the most.

No one-size-fits-all window

Breaking funding down into different modalities, LDCs have proposed three windows for access to the LDF:

- A rapid disbursement window for immediate responses to extreme events, including early recovery;

- An intermediate window for supporting rehabilitation and reconstruction (including building back better) from a specific extreme event; and

- A chronic needs window for programmatic grants for rehabilitation and other relevant activities to address the effects from slow onset events and ongoing impacts.

However, there remains an issue with the windows being global: a one-size-fits-all solution is problematic.

Having global LDF windows unfortunately makes it likely that larger Developing Countries, with greater human and technical capacity to access funds, will effectively be able to receive a greater share.

We have seen this kind of thing happen before — as in the case of the Green Climate Fund, where LDCs and SIDS receive a small share of the available financing compared to larger Developing Countries.

Given this precedent, it may arguably be more beneficial to have separate, dedicated windows for larger Developing Countries, LDCs and SIDS, all managed under the banner of the LDF global windows.

This will ensure that LDCs and SIDS would not need to compete with the larger Developing Countries, or potentially each other, when desperate to access funding after experiencing damage from a climatic event.

Keep it simple; make it fast

In all of this, though, some priorities remain key, whatever the process: the submission template countries use to access the LDF needs to be simple to complete; and the funds need to be disbursed quickly.

For the LDF to be fit for purpose, those two basic needs are non-negotiable: keep it simple; make it fast.

Diary Date: 8-10 April — upcoming meeting of the Board of the Fund for responding to loss and damage.

Kelly Hunte is a Programme Analyst attached to the Demonstration of a Caribbean Mechanism Toward Establishment of a SIDS Green Blue Economy Knowledge Transfer Hub, based in Barbados. As an economist passionate about climate finance, she brings to the table a wealth of experience and expertise in economic development issues and has served on panels for the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC).

Further Reading:

- More about the Loss and Damage Fund (LDF) announced at COP27; then formally agreed at COP28;

- More on origins of the LDF in the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage (WIM);

- More on LDF development in Article 8 of the Paris Agreement;

- More about the Green Climate Fund (GCF);

- Also on SustMeme, Nature-based solutions on the rise in Africa;

- Also on SustMeme, Season 28 of the greatest COP show on Earth;

- Also on SustMeme, Ultra-early wildfire detection raises pilot-site alarm;

- Also on SustMeme, Ageing dams pose growing threat made worse by climate change;

- Also on SustMeme, Half of humanity affected by land degradation;

- Also on SustMeme, Flood risk: ‘Future of Infrastructure’ in ‘The Times’;

- Also by Kelly Hunte on SustMeme, Guest Blog: Can private money save the Green Climate Fund?

- Also by Kelly Hunte on SustMeme, Guest Blog: Is the new Climate Goal just smoke and mirrors?

- Also by Kelly Hunte on SustMeme, Guest Blog: Key role for third sector in climate finance.

You can check out the full archive of past Guest Blog posts here.

Would you like to Guest Blog for SustMeme? For more info, click here.

SUSTMEME: Get the Susty Story Straight!